Hyperinflation is one of the most destructive economic phenomena a country can experience. It can push the economy into a deep crisis and dramatically alter citizens’ lives. This situation weakens the national economy and destroys individual wealth.

Understanding hyperinflation, its causes, and how to respond is crucial for anyone concerned about financial stability. This guide examines hyperinflation, its causes, damaging consequences, and ways people and policymakers address it.

- In hyperinflation, the velocity of money rises sharply because people try to spend cash before it loses even more value.

- The economy often shifts towards dollarisation or barter transactions (goods-for-goods instead of money).

- Government tax revenues effectively evaporate because of the time lag between when tax liabilities arise and when taxes are actually collected.

- Prices may change not just daily but hourly, making normal price labelling almost impossible.

What Is Hyperinflation?

Hyperinflation is an economic condition where the inflation rate rises rapidly and becomes uncontrolled. In financial terms, hyperinflation occurs when monthly inflation exceeds 50%, roughly corresponding to an annual rate of 12,875%. Source: financestrategists According to Wikipedia, under these conditions, the domestic currency loses value quickly, and households’ purchasing power erodes severely. During hyperinflation, people try to hold as little local currency as possible. They shift into more stable foreign currencies or real assets, such as gold. This behaviour increases the velocity of money and creates a vicious cycle. Prices keep rising, the currency loses value faster, and the economy enters a self-reinforcing spiral.When Does Inflation Turn into Hyperinflation?

Inflation becomes hyperinflation when price increases are so extreme that the national currency collapses. According to economist Philip Cagan, hyperinflation begins when monthly inflation exceeds 50%. It ends only after inflation falls below 50% and remains under that level for at least one year. The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) has also specified indicators for identifying a hyperinflationary environment in IAS 29 Financial Reporting in Hyperinflationary Economies (IFRS Foundation), including:- Flight from the local currency: The public prefers to hold its wealth in non-monetary assets or in reputable foreign currencies, and rapidly converts cash into other assets to preserve purchasing power.

- Foreign currency as a reference unit: People measure the value of goods and services in a more stable foreign currency, and prices may even be quoted directly in that currency.

- Compensatory pricing in credit transactions: In credit sales, prices are set in a way that compensates for the severe loss of the currency’s value over the repayment period.

- Indexation to inflation: Wages, interest rates, and prices are directly linked (indexed) to a price index or the inflation rate.

- High cumulative inflation: Cumulative inflation over a three-year period reaches about 100% or more.

The Difference Between High Inflation, Chronic Inflation, and Hyperinflation

To understand hyperinflation more clearly, it helps to distinguish it from high inflation and chronic inflation:

- High inflation: Typically refers to an annual inflation rate above about 20%. Prices rise quickly, but the economy can still function relatively normally, and households and businesses are still able to make medium- to long-term financial plans.

- Chronic inflation: Describes a situation where inflation remains at a high level (for example, between 10% and 30% per year) for an extended period, usually several years. In this environment, people become accustomed to continuous price increases and, despite ongoing problems, the economy continues to operate.

- Hyperinflation: In this case, inflation is so extreme that the national currency is rapidly losing its value. Prices may multiply several times within a single day, and people avoid holding the local currency altogether. The economy becomes highly unstable, and normal economic activity is severely disrupted.

Economic research shows hyperinflation usually occurs with severe budget deficits financed by money printing. Swiss economist Peter Bernholz found that in 25 of 29 cases, deficits financed by printing money caused hyperinflation.

Root Causes and Main Drivers of Hyperinflation in an Economy

Hyperinflation is a destructive economic phenomenon caused by a combination of mismanagement and structural economic pressures.

Expansionary monetary policy and excessive money creation

When a government turns to the central bank to cover budget deficits, and money creation outpaces real output growth, inflationary pressure begins. Monetarist theories explain that in low-confidence environments, the money supply increases and the velocity of money also rises. As a result, the overall price level can climb faster than the rate at which new money is printed.

What is the velocity of money, and how does it affect hyperinflation?

The velocity of money refers to how often money changes hands in the economy. When people try to spend cash quickly, the velocity rises, intensifying inflation.

High public debt and chronic fiscal deficits

When a government cannot collect taxes efficiently or borrow at reasonable rates, printing money becomes the easiest way to cover deficits. If combined with rigid spending, like public wages, subsidies, or war costs, the economy may enter a self-reinforcing inflationary spiral.

Loss of public confidence in the national currency

Once the economy passes a critical threshold, people no longer wish to hold the domestic currency. In this situation, sellers demand a “risk premium” to accept local money or set prices in real time based on trusted foreign currencies. This collapse in confidence, seen in cases such as Venezuela and Zimbabwe, makes the currency’s fall in value effectively uncontrollable.

The impact of political crises, wars, and sanctions on severe inflation

War or political instability simultaneously reduces government revenues (such as tax income) and sharply increases expenditures. This raises the government’s sovereign credit risk and forces it to resort to money printing to finance. Historical examples of this pattern are documented in China (1940s), Greece (1940s), and Yugoslavia (early 1990s).

The role of weak production and import dependence in amplifying inflation

In import-dependent economies, supply shocks, like declining domestic production or import restrictions, significantly increase upward pressure on prices. If exchange rates rise due to foreign currency shortages, imported goods become more expensive. This higher cost spreads quickly through the economy, creating acute inflation.

Economic and Social Consequences of Hyperinflation

Hyperinflation is more than a purely monetary phenomenon; it rapidly destroys the foundations of the economy and the psychological fabric of society.

Depreciation of the Currency and Loss of Purchasing Power

The most direct consequence of hyperinflation is the rapid loss of purchasing power. In such conditions, prices rise much faster than nominal wages.The “life span of price tags” becomes extremely short, with prices changing daily or even hourly.

Historical episodes illustrate the severity of this disaster. In Germany (1923), money lost so much value that banknotes were reportedly used as wallpaper. Records show Hungary (1946) and Zimbabwe (2008) issued banknotes with astronomical denominations, reflecting complete loss of currency credibility.

Destruction of Savings and Capital Flight

Hyperinflation wipes out cash savings and acts as a heavy tax on money holders, especially retirees and fixed-income groups. In response to negative real interest rates, households and firms buy physical assets or foreign currencies to preserve wealth. This behaviour triggers large-scale capital flight, deepening the crisis of scarce financial resources.

How does hyperinflation affect the housing market differently than the consumer goods market?

The housing market typically responds more slowly, and its value changes more gradually compared to everyday consumer goods. This makes real estate a relatively stable store of value during hyperinflation, but it still requires careful liquidity management and risk planning.

Market Instability and Decline in National Output

Extreme price uncertainty darkens producers’ planning horizon. When firms are unable to forecast future costs and selling prices, investment stalls and inventory management is severely disrupted.

The result is stagflation: an environment in which the economy suffers from high inflation alongside a sharp decline in output and rising unemployment. The economic experiences of Venezuela and Zimbabwe are prominent examples of this destructive cycle, in which national production becomes a casualty of market instability.

Social and Psychological Consequences of Hyperinflation

The constant pressure of trying to secure necessities plunges society into chronic anxiety and hopelessness. This environment fuels extreme precautionary behaviours such as panic buying.

At a broader level, hyperinflation destroys public trust in government and economic institutions. The erosion of social capital, rising poverty, and a growing sense of economic vulnerability can create fertile ground for higher crime rates and even civil and political unrest.

Historical research shows hyperinflation often causes severe social consequences. In 1923 Germany, it increased poverty, insecurity, and contributed to radical political movements, playing a key role in the rise of Nazism and Hitler.

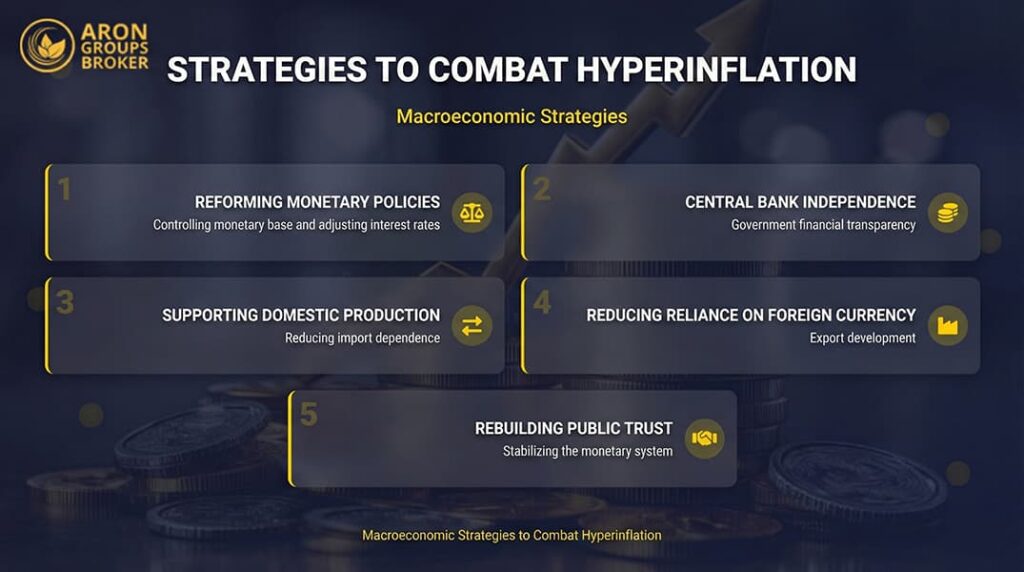

Policy Responses to Hyperinflation at the Macroeconomic Level

Containing hyperinflation requires the simultaneous implementation of a disciplined policy package that eliminates the monetary roots of the crisis and restores lost confidence among economic agents.

Reforming Monetary Policy and Controlling the Monetary Base

The first and most critical step is to immediately halt monetising the fiscal deficit, meaning the government must stop financing its expenditure by drawing on central bank resources.

Returning to standard frameworks such as inflation targeting requires implementing smart, contractionary policies, including higher real interest rates and strict control over money supply growth. Although these measures are painful in the short term, they are essential for breaking the core of inflation.

Central Bank Independence and Fiscal Transparency

To resist political pressure to print money, the central bank needs legal independence. It must be able to enforce monetary discipline without fear of political repercussions.

At the same time, the government must ensure full fiscal transparency. This includes regular reporting and disclosure of off-balance-sheet or hidden liabilities. Such transparency allows citizens and international institutions to realistically assess its performance.

This transparency sends a strong signal that the government is serious about rebuilding its damaged credibility with market participants.

Supporting Domestic Production and Reducing Dependence on Foreign Currency

Supporting the supply side by removing production bottlenecks, improving access to raw materials and energy, and strengthening domestic supply chains helps reduce price pressures. Reducing structural reliance on imports increases economic resilience to exchange rate shocks and limits how currency fluctuations pass through to domestic prices.

Redirecting financial resources from speculative and intermediary activities to productive sectors is a key to success in this area.

Rebuilding Public Confidence in the Monetary System

Historical experience shows that after initial inflation control, symbolic yet effective measures can help stabilise public sentiment. These measures include currency reform or removing zeros from banknotes, as seen in Brazil’s 1994 Real Plan.

Some countries, like Ecuador and Zimbabwe (According to the Daily Economy), halted hyperinflation by abandoning their national currency and adopting a foreign currency. This strategy can stop inflation but sacrifices the country’s monetary sovereignty.

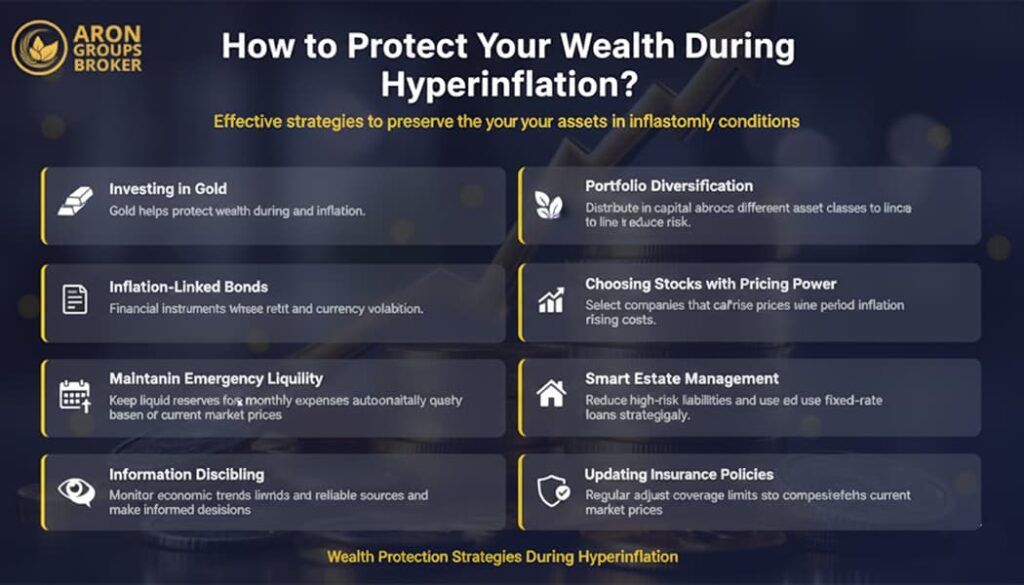

How to Protect Your Wealth During Hyperinflation

- Diversify your asset portfolio: Diversify your wealth by allocating it across reputable foreign currencies, real assets like real estate, durable goods, and financial assets to reduce risk.

- Invest in gold: Historically, gold has acted as a “safe haven” during inflationary periods. However, always consider the risks of physical storage and any applicable domestic regulations.

- Choose stocks with strong pricing power: In the stock market, focus on companies that can raise prices alongside rising production and operating costs. However, remain cautious of sharp short-term volatility in equity markets.

- Use inflation-linked securities: Where available (as in some global markets), allocate part of your capital to bonds whose returns are automatically adjusted in line with inflation.

- Manage real estate intelligently: In rental contracts, include clauses that allow for periodic adjustments of rent based on reliable inflation indices so that the real value of rental income is preserved.

- Maintain emergency liquidity: Keep the equivalent of 3 to 6 months of essential expenses in a form (such as reputable foreign currencies) that both preserves value against price shocks and can be converted to cash quickly.

- Manage debt carefully: In a hyperinflationary environment, the real value of fixed-rate loans declines (benefiting the borrower). However, you should not ignore the risks of potential interest rate adjustments by banks or your own reduced repayment capacity.

- Use short-term budgeting: When prices change rapidly, annual financial plans lose their effectiveness. Review and adjust your budget on a monthly or quarterly basis in line with current prices.

- Update your insurance coverage: Given sharp price increases, regularly raise the coverage limits of your insurance policies (such as property or life insurance) so that, in the event of a loss, compensation reflects current replacement values.

- Practice information discipline: For financial decision-making, rely on credible sources and official economic data such as reports from international institutions instead of rumours and unverified market chatter.

Hyperinflation in Iran: Reality or Potential Threat?

At present, Iran’s economy is facing high and chronic inflation, not full-scale hyperinflation. According to the Statistical Centre of Iran, by September 2025:

- Annual inflation had reached 45.3%.

- Monthly inflation had risen to 3.8%.

These figures signal intense pressure on household living standards and a continuous erosion of purchasing power. However, based on Philip Cagan’s definition, as long as:

- Monthly inflation does not exceed 50%, and

- Public confidence in the national currency has not collapsed on a broad scale,

The current situation cannot be classified as genuine hyperinflation.

Iran is effectively standing at a threshold of warning. If:

- Monetary policy reforms are delayed,

- Liquidity growth is not controlled, and

- Public trust in the national currency has not been rebuilt,

The current environment could quickly deteriorate into true hyperinflation.

In such conditions, managing inflation expectations and strengthening domestic production are essential to prevent currency collapse and wider economic instability.

Global Examples of Hyperinflation

Here is a list of some of the most important and widely known hyperinflation episodes in world history, with a brief explanation for each case:

Germany (Weimar Republic) – 1923

- Period: 1921 to 1923

- Peak: November 1923

After World War I, Germany began printing money on a massive scale to pay heavy war reparations. This led to one of the most famous hyperinflation episodes in history. Prices rose so quickly that people carried their wages in suitcases or wheelbarrows and spent them immediately. At the height of the crisis, prices were doubling every few days.

Hungary – 1945-1946

- Period: 1945 to 1946

- Peak: July 1946

After World War II, Hungary experienced the worst recorded hyperinflation in history. War damage, destruction of infrastructure, and reparations to the Soviet Union crippled the economy. At the peak, prices were doubling roughly every 15 hours. The government printed banknotes with astronomical denominations (such as 100 quintillion pengő) until a new currency, the forint, was finally introduced.

Zimbabwe – Late 2000s

- Period: Around 2007 to 2008

- Peak: November 2008

Misguided economic policies, failed land reforms, and massive money printing under the Mugabe government led to severe hyperinflation. Inflation rose so high that a 100 trillion-dollar banknote was issued, which in practice had almost no purchasing power. Eventually, Zimbabwe abandoned its national currency and began using foreign currencies such as the US dollar.

Yugoslavia – Early 1990s

- Period: 1992 to 1994

- Peak: January 1994

The breakup of Yugoslavia, civil wars, international sanctions, and economic mismanagement triggered extreme hyperinflation in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro). To finance war expenditures and budget deficits, the government resorted to printing money. Prices were rising sharply, almost daily.

| Country / Period | Hyperinflation Period | Peak | Key Causes | Notable Effects | Resolution / Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany (Weimar Republic) | 1921–1923 | Nov 1923 | Post-WWI reparations, massive money printing | Prices doubled every few days; wages carried in suitcases | Hyperinflation ended after currency reform (Rentenmark) |

| Hungary | 1945–1946 | July 1946 | War damage, infrastructure destruction, reparations to USSR | Prices doubled every ~15 hours; astronomical banknote denominations | Introduced new currency, the forint |

| Zimbabwe | 2007–2008 | Nov 2008 | Failed land reforms, economic mismanagement, massive money printing | 100 trillion-dollar notes issued; near-zero purchasing power | Abandoned national currency; adopted foreign currencies like USD |

| Yugoslavia | 1992–1994 | Jan 1994 | Breakup of Yugoslavia, civil wars, sanctions, economic mismanagement | Prices rose almost daily; extreme instability | Stabilized after economic reforms and new currency measures |

| Venezuela | From 2016 onwards | Fluctuating | Oil price collapse, corruption, economic mismanagement, sanctions | Bolívar collapsed; shortages of food and medicine; repeated zero removal from currency | Ongoing; attempts to stabilize continue |

| Argentina | Multiple periods (including late 1980s, recent crises) | Varies | Heavy external debt, chronic fiscal deficits, political instability | Inflation often exceeded 100%; repeated crises | Ongoing; partial stabilization with monetary and fiscal policies |

Venezuela – From 2016 Onwards

- Period: Starting around 2016, continuing with fluctuations

A sharp fall in oil prices (the country’s main source of revenue), economic mismanagement, corruption, and international sanctions drove Venezuela into hyperinflation. The value of the national currency, the bolívar, collapsed, and people have faced severe shortages of food and medicine. The government has repeatedly removed zeros from the currency in an attempt to keep the system functioning.

Argentina – Multiple Periods

- Period: Argentina has gone through several episodes of very high inflation and hyperinflation, including the late 1980s and more recent crises.

A combination of heavy external debt, chronic fiscal deficits, political instability, and weak confidence in the national currency has driven Argentina’s repeated inflation crises. In recent years, annual inflation has surged again, frequently exceeding 100 percent.

Other Notable Cases

- China (1948–1949): During the civil war, the Nationalist government financed military spending by printing money, which led to hyperinflation, economic collapse, and ultimately contributed to the Communist victory.

- Bolivia (1984-1985): A debt crisis and large fiscal deficits triggered hyperinflation, which was later brought under control through drastic economic reforms.

- Greece (1941-1944): Under Nazi occupation, the plundering of resources and large-scale money printing by the occupying forces caused severe hyperinflation.

Conclusion

Hyperinflation is a destructive phenomenon that rapidly erodes social welfare and undermines public trust. Combating it requires restoring fiscal and monetary discipline, ensuring central bank independence, and rebuilding lost confidence.

To protect wealth, households and businesses must adopt practical strategies during periods of severe economic instability. These include diversifying asset portfolios, holding multiple currencies and physical assets, indexing contracts to inflation, and using short-term budgeting.

Historical experience shows that hyperinflation can be controlled with reliable data, transparent policymaking, and deep structural reforms.