Inflation is one of the most influential forces driving economic conditions, shaping investment decisions, affecting currency valuations, and guiding central bank policies. Whether prices are rising moderately or rapidly, inflation changes how consumers spend, how companies plan, and how traders and investors manage risk. Understanding what inflation is, how it works, and why it matters is essential for anyone navigating the modern financial world.

This comprehensive guide breaks down the foundations of inflation, from measurement tools such as CPI to major causes like demand-pull and cost-push dynamics, while exploring how inflation influences markets, currencies, and long-term investment strategies.

- Inflation quietly shifts wealth: it usually helps borrowers and hurts cash savers and fixed-income holders.

- Expectations matter: if people expect higher inflation, they often raise wages and prices, making it real.

- Tax systems lag inflation, causing “bracket creep” where people pay more tax without a higher real income.

- Inflation changes prices unevenly, distorting signals for businesses and investors about true demand.

What is Inflation?

Inflation refers to the general increase in the prices of goods and services over time. When inflation rises, each unit of currency buys less than it did previously, a phenomenon known as a decline in purchasing power. Economists typically define inflation as a sustained rise in the overall price level, rather than short-term fluctuations.

Inflation is usually expressed as an annual percentage. For example, if inflation is 5%, consumers will pay 5% more for a similar basket of goods than they did the previous year.

Types of Inflation Based on Price Behavior

Economists classify inflation based on severity:

- Creeping inflation (mild): 1–3% annually; considered normal and manageable.

- Walking inflation (moderate): 5–10% annually; purchasing power declines more noticeably.

- Galloping inflation (high) : Double-digit inflation; often destabilizing and harmful to businesses and households.

Extreme cases, beyond galloping, fall under the category of hyperinflation, discussed later in this article.

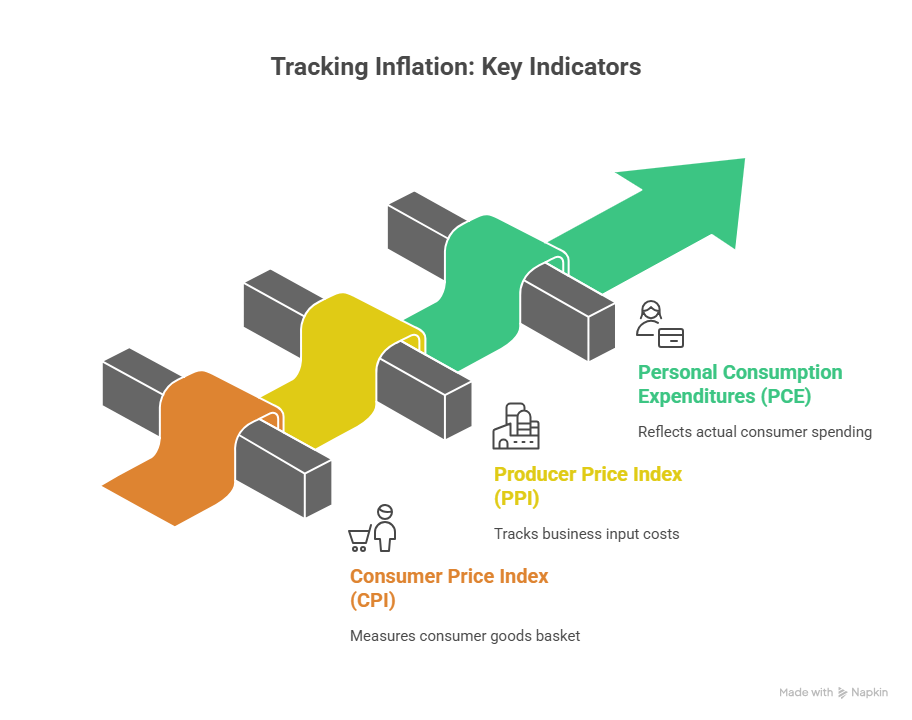

Key Indicators Used to Track Inflation

Governments and statistical agencies use price indices to measure inflation. These indices track the cost of a representative “basket” of goods and services purchased by consumers or businesses.

According to Brookings Institution,the most commonly used measures include:

- Consumer Price Index (CPI);

- Producer Price Index (PPI);

- Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index.

Each index measures different segments of the economy.

According to bis.org, beyond rising prices, inflation alters the structure of markets by changing discount rates, disrupting inter-market correlations, and redefining what investors consider safe.

Consumer Price Index (CPI)

The CPI is the most widely recognized inflation measure. It tracks the average change in prices paid by urban consumers for a fixed basket of goods and services, including:

- Housing;

- Food;

- Transportation;

- Medical care;

- Education.

CPI heavily influences wage negotiations, adjustments to social benefits, and monetary policy decisions.

Producer Price Index (PPI) and Its Relationship to CPI

PPI tracks the prices producers receive for their output. It is considered a leading indicator because changes in producer prices often show up later in consumer prices.

For example, if raw materials or manufacturing costs rise, businesses may pass those costs on to consumers, thereby raising CPI.

Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index

The Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index is a major U.S. inflation indicator compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). While it is not a global standard, it plays a central role in U.S. economic policy, particularly because the Federal Reserve uses the PCE, and especially the core PCE, as its primary inflation target.

Unlike the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which measures the out-of-pocket expenses of urban consumers, the PCE covers a broader and more comprehensive set of expenditures. It includes both direct household spending and indirect expenditures, such as employer-funded or government-funded healthcare services. This broader scope allows the PCE better to reflect changes in consumption across the entire economy.

Hidden inflation can emerge through product downsizing or quality reductions, a phenomenon known as ‘shrinkflation.

Another key feature of the PCE is its substitution adjustment, which captures shifts in consumer behaviour when relative prices change, for example, when households switch from more expensive goods to cheaper alternatives. The CPI does not account for these substitutions, making the PCE generally smoother and more reflective of real-world consumption dynamics.

Because the core PCE (which excludes volatile components like food and energy) provides a more stable and reliable view of underlying inflation trends, it is the measure the Federal Reserve relies on when setting monetary policy. As a result, financial analysts and investors closely track PCE data, as its monthly releases can significantly influence expectations for interest rate decisions and broader economic conditions.

Core Inflation vs. Headline Inflation

Headline inflation measures the overall change in the consumer price basket, including all categories such as food and energy. Because these components are highly volatile, headline inflation can fluctuate sharply in the short term.

Core inflation excludes food and energy prices to provide a more precise and more stable view of underlying inflation trends. By filtering out temporary price swings, it better reflects the long-term trajectory of inflation.

Central banks, including the U.S. Federal Reserve, typically rely on core inflation when setting interest rates. Since it is less volatile and better captures persistent inflationary pressures, core inflation offers a more reliable indicator for monetary policy decisions.

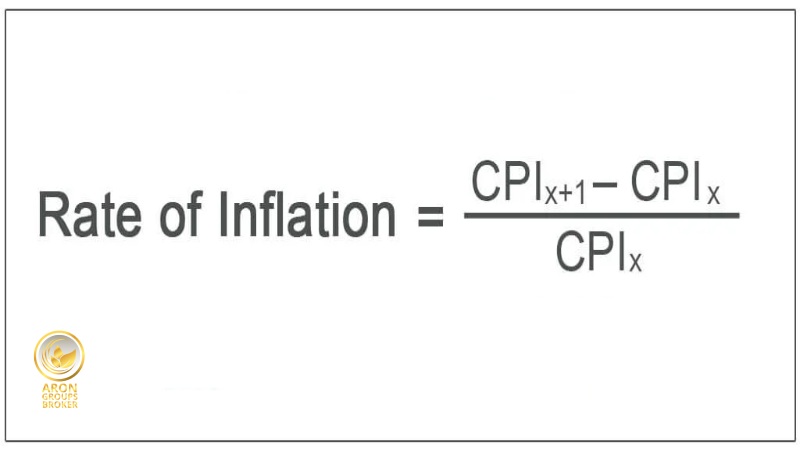

Inflation Calculation

The inflation rate is usually calculated by measuring the change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) over two time periods. The standard formula is:

Inflation rate = (CPIx+1 − CPIx) / CPIx × 100

Where:

- CPI at end of period (CPIx+1):

The Consumer Price Index at the end of the period under review, for example, at the end of the year. - CPI at start of period (CPIₓ):

The Consumer Price Index at the beginning of the period, for example, at the start of the year.

Main Causes of Inflation

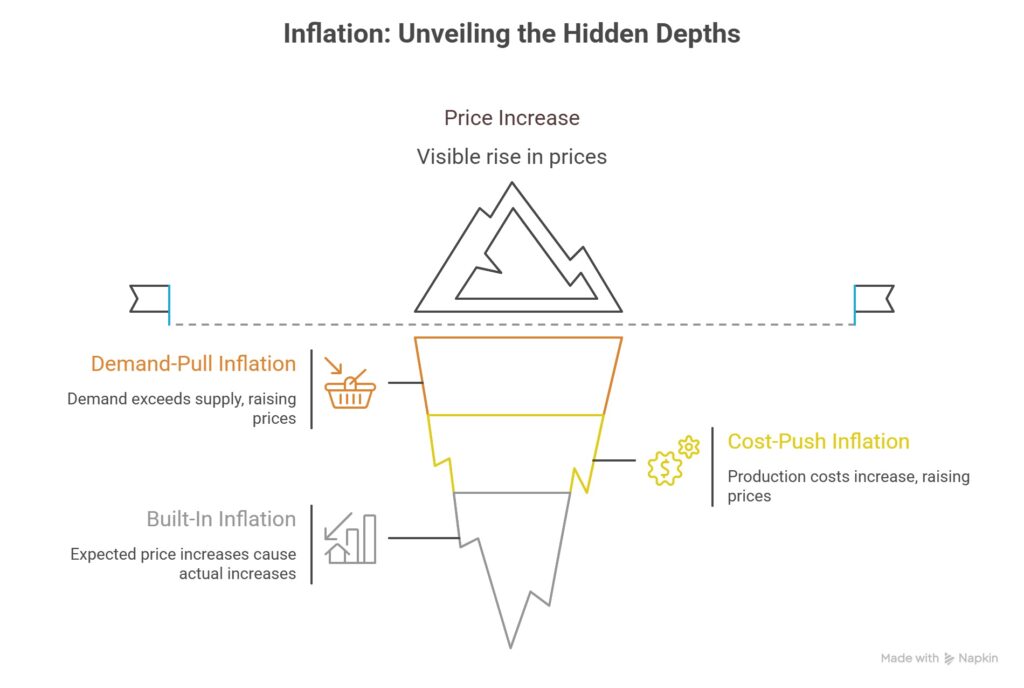

Inflation does not arise from a single source. Economists categorize its main causes into three major frameworks:

Demand-Pull Inflation

Demand-pull inflation occurs when aggregate demand exceeds an economy’s productive capacity. When consumers, businesses, and governments collectively spend more than the economy can produce, prices naturally rise.

Common drivers include:

- Economic expansion;

- Excessive government spending;

- High consumer confidence;

- Easy monetary policy and low interest rates.

Cost-Push Inflation

Cost-push inflation results from rising production costs that force businesses to raise prices to maintain profitability. These costs may include:

- Higher wages;

- Increased raw material prices;

- Supply chain disruptions;

- Currency depreciation (which raises import costs).

The supply shocks of 2021–2022, driven by global shipping shortages, semiconductor deficits, and energy price spikes, are prime examples.

Built-In Inflation

Built-in inflation occurs when workers demand higher wages to keep up with rising living costs, and businesses then raise prices again to cover the higher labor costs. This cycle can sustain inflation even in the absence of external shocks.

Economic Phenomena Related to Inflation

Inflation does not exist in isolation; closely related concepts such as deflation, stagflation, and hyperinflation help illustrate how price levels can behave under different economic environments.

Inflation vs. Deflation: Key Differences

To clearly understand how each condition shapes economic behavior, it’s essential to distinguish the core characteristics of inflation and deflation:

- Inflation: Prices rise; purchasing power falls.

- Deflation: Prices fall; purchasing power increases.

While deflation might seem beneficial for consumers, persistent deflation can trigger lower consumption, reduced business investment, and long-term economic stagnation. The Bank of Japan’s long struggle with deflation is a well-documented example.

Stagflation: High Inflation with Low Growth

Stagflation occurs when high inflation is accompanied by weak economic growth and high unemployment. This rare and problematic combination first gained attention during the 1970s oil crisis.

Key characteristics of Stagflation:

- Rising prices;

- Declining productivity;

- Weak labor markets.

Stagflation poses a significant challenge because traditional monetary tools that reduce inflation may worsen unemployment, and vice versa.

Hyperinflation: Extreme and Rapid Price Increases

Hyperinflation is typically defined as monthly inflation exceeding 50%. It devalues currencies, erodes savings, and destabilizes economies. Widely studied examples include:

- Zimbabwe (2000s);

- Venezuela (2010s);

- Weimar Germany (1920s).

How Inflation Impacts Currencies and Financial Markets

As inflation rises or falls, it inevitably influences currency values and the performance of major financial markets, shaping investor behavior across stocks, bonds, and commodities.

The Relationship Between Inflation and Exchange Rates

According to Investopedia, higher inflation typically weakens a currency over time because reduced purchasing power makes a currency less attractive to global investors. Forex markets react strongly to inflation data releases (CPI, PPI), especially when the numbers deviate from expectations.

Central banks often combat inflation by raising interest rates, which can temporarily strengthen a currency by attracting foreign capital.

Small but persistent inflation biases tax brackets over time, quietly increasing effective taxation without new legislation.

Effects of Inflation on Stocks, Bonds, and Commodities

Because inflation affects corporate profits, interest rates, and real asset valuations differently, its impact varies significantly across major asset classes:

Stocks

Moderate inflation can be positive for equities, especially if companies can pass higher costs to customers. But high inflation increases uncertainty, reduces consumer spending power, and compresses valuation multiples.

Bonds

Inflation is generally negative for fixed-income securities. As inflation rises, bond yields increase, and existing bond prices fall.

Commodities

Commodities, particularly gold, oil, and industrial metals, often outperform during inflationary periods because they serve as real assets that retain value.

Impact of Inflation Expectations on Market Sentiment

Financial markets react not only to actual inflation data but also to inflation expectations. When consumers and businesses expect higher inflation, they adjust their behaviour; demanding higher wages, raising prices, or shifting investments, which can, in turn, create additional inflationary pressure.

Breakeven inflation rates (calculated from TIPS spreads) are a widely used indicator of market expectations.

Inflation and Monetary Policy

Central banks play a crucial role in managing inflation, using interest rates, balance-sheet tools, and policy guidelines to keep price growth within desirable limits.

How Central Banks Use Interest Rates to Control Inflation

Central banks aim to keep inflation stable, predictable, and aligned with long-term economic goals. Their primary tool for influencing inflation is adjusting policy interest rates, which directly affects borrowing costs, liquidity, and overall economic demand.

When central banks raise interest rates, borrowing becomes more expensive for households and businesses, reducing spending and investment—ultimately easing inflationary pressures. Conversely, lowering interest rates makes credit cheaper, stimulates consumption and investment, and can help push inflation higher when it is too low.

Quantitative Tightening (QT) and Money Supply Management

Quantitative Tightening (QT) is another major tool used to combat inflation. In QT, central banks reduce the size of their balance sheets by selling government securities or allowing them to mature without reinvestment. This process effectively withdraws liquidity from the financial system.

As liquidity decreases:

- Borrowing becomes more expensive;

- financial conditions tighten;

- asset prices may come under pressure, and

- Overall demand in the economy slows.

By reducing the money supply and tightening financial conditions, QT works alongside interest rate hikes to bring inflation back toward target levels.

Why Targeting 2% Inflation Is Considered Optimal

Most major central banks—including the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the Bank of England—target an annual inflation rate of around 2%. This target is widely seen as the sweet spot for long-term economic stability.

A 2% inflation rate is considered optimal because it:

- Supports healthy economic growth by encouraging moderate spending and investment.

- Prevents deflation, which can cause consumers to delay purchases and businesses to cut production.

- Preserves purchasing power over time by keeping price increases predictable.

- Maintains financial stability, helping investors and firms make long-term plans with greater confidence.

Real-World Examples and Case Studies

Real-world examples of inflation offer valuable lessons, showing how different economies have experienced and managed price surges across various historical and geopolitical contexts.

- Hyperinflation cases show how quickly economic systems can deteriorate when inflation becomes uncontrollable. Lessons from Zimbabwe, Venezuela, and Weimar Germany highlight the importance of responsible fiscal and monetary policy.

- Before the pandemic, U.S. inflation remained stable at around 2%. However, stimulus packages, supply chain disruptions, and energy shocks after 2020 led to inflation surging to multi-decade highs in 2021–2022.

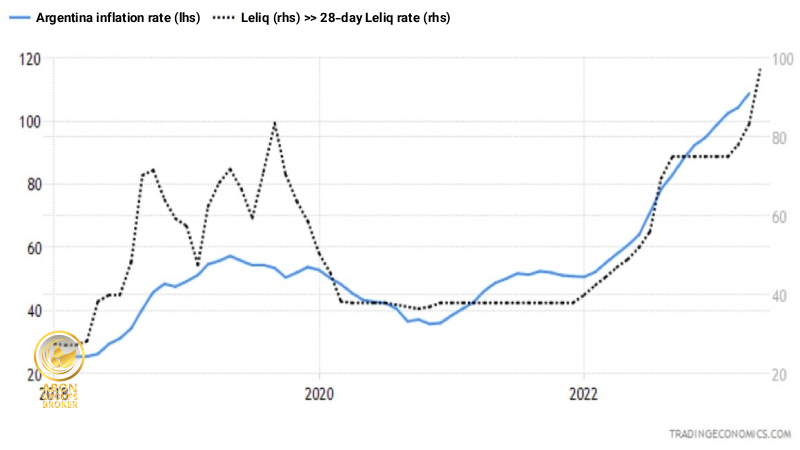

How Emerging Markets Respond to Inflation Shocks

Emerging markets often face more severe inflation volatility due to:

- Currency depreciation;

- Commodity-driven economies;

- Capital flow sensitivity.

Many central banks in Latin America and Asia implemented aggressive rate hikes during 2021–2023 to stabilize their currencies and control inflation.

How Investors and Traders Can Manage Inflation Risk

For individuals and traders, understanding inflation is only half the challenge. The next step is learning how to protect portfolios and capitalize on market opportunities during inflationary cycles.

Hedging Strategies

In periods of rising inflation, investors often turn to specific hedging instruments that have historically preserved value as the purchasing power of fiat currencies weakens. Below are the most commonly used inflation hedges and why they matter.

Gold

Gold has traditionally served as a reliable hedge against currency devaluation and long-term inflation. Because it is a scarce physical asset with intrinsic value, gold tends to maintain—or even increase—its purchasing power during periods of monetary instability.

TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities)

Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities are U.S. government bonds designed specifically to safeguard investors from inflation. The principal value of TIPS adjusts with changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), ensuring that both interest payments and the final repayment reflect real inflation-adjusted value.

Commodities

Commodities such as energy (oil and natural gas), industrial metals, and agricultural products often perform strongly during inflationary cycles. Since commodity prices are directly tied to production costs and supply and demand dynamics, they tend to rise when overall prices rise.

Portfolio Allocation in High-Inflation Environments

Constructing a resilient portfolio during high-inflation periods requires strategic shifts toward assets that either benefit from inflation or are less sensitive to rising interest rates. Investors typically consider the following adjustments to protect returns and reduce risk exposure:

- Increasing allocation to real assets such as real estate, commodities, and inflation-linked bonds;

- Reducing exposure to long-duration bonds, which lose value as interest rates rise;

- Prioritizing value stocks and cyclical sectors (e.g., energy, financials, materials) that often outperform during inflationary expansions;

- Diversifying into international markets, especially economies with stronger currencies or lower inflation dynamics.

These tactics help balance risk while improving overall portfolio resilience in challenging macroeconomic environments.

How Forex Traders Use Inflation Data for Market Analysis

Inflation plays a major role in determining currency strength because it directly influences central bank interest rate decisions. For forex traders, this leads to clear and actionable market behaviour.

- When inflation comes in higher than expected, markets often anticipate potential interest rate hikes. This typically strengthens the currency, and traders may look for long opportunities in pairs such as USD/JPY or GBP/USD.

- When inflation is lower than expected, expectations for tighter monetary policy weaken. As a result, the currency usually loses value, and traders may consider short positions in pairs like EUR/USD or AUD/USD.

Inflation surprises frequently trigger sharp short-term volatility, creating opportunities for breakout or momentum trades. Over the medium term, consistent inflation trends help traders align their positions with likely central bank policy shifts.

Conclusion

Inflation is more than just an economic concept—it is a fundamental driver of financial decision-making, consumer behaviour, and market dynamics. Whether inflation rises gradually or spikes due to external shocks, understanding its causes, indicators, and effects allows investors, traders, and policymakers to respond effectively.

By monitoring leading indicators, analyzing policy actions, and applying smart investment strategies, market participants can protect their capital and make informed decisions in any inflationary environment.